Beneath the Mask: The Fall of Anakin Skywalker and the Rise of Darth Vader

Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering.

Yesterday, May the 4th, was Star Wars Day. The story of Star Wars is the story of Anakin Skywalker, the Chosen One, who brings balance to the Force. Anakin Skywalker is regarded by many as the most tragic character in fiction. After studying Cluster B personality disorders, I’ve come to see his fall in a different light. Perhaps if Anakin had received the right emotional support or therapy, his descent into the Dark Side could have been prevented.

Anakin displays core traits of both Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD). These two often overlap, and Anakin also exhibits histrionic and antisocial features. In this piece, I’ll break down why Anakin was particularly vulnerable to manipulation, obsession, and violence due to his Cluster B personality structure and how his fears, attachments, and identity struggles drove him to the Dark Side.

This is the video that made me a Star Wars fan:

Fear

At the heart of narcissism lies a core fear of being fundamentally inadequate, unworthy, or unlovable. For those with borderline traits, the central fear is abandonment. Anakin carries both. Anakin developed both of these fears as a result of profound early trauma. Born into slavery and raised without a father, he was subjected to chronic helplessness, emotional deprivation, and objectification—conditions that instill toxic shame and fracture the developing self. Slavery didn’t just limit Anakin’s freedom; it taught him that his value depended on his utility, not his inherent worth. His only source of love and security, his mother, Shmi—was abruptly taken from him when the Jedi removed him from Tatooine. The blow was compounded by the death of Qui-Gon Jinn, who had briefly served as a surrogate father figure. These losses left Anakin emotionally unanchored, with no stable attachment figures and no internalized sense of safety. From this fractured foundation grew the desperate hunger for validation, control, and closeness that would define his adult relationships—and ultimately, his downfall.

Narcissistic Ambition and Competitiveness

Another key factor that contributed to Anakin’s narcissism was his destiny as the Chosen One. From a young age, he was told he would destroy the Sith and bring balance to the Force. This prophecy set him apart and inflated his sense of importance. He was also informed that his midi-chlorian count surpassed even Master Yoda’s (over 20,000!), reinforcing the belief that he was uniquely powerful and destined for greatness. Repeatedly being told that one is “special” fosters a narcissistic self-concept, particularly in individuals already struggling with identity and insecurity. When someone internalizes the idea that they are exceptional, they begin to view themselves as above the rules, justified in bending moral codes or prioritizing their desires over the well-being of others. Anakin exemplifies this pattern: he frequently defies Jedi orders, endangers others, and acts on impulse.

As the Clone Wars progresses, his behavior becomes increasingly Machiavellian as he seeks to secure the power he believes is rightfully his. Narcissists are hyper competitive and feel the need to prove themselves or show off. They are afraid to lose. Anakin’s narcissistic ambition is rooted in a deep need to prove his worth—not just to others, but to himself. Because he believes he is destined for greatness, this narrative quickly fused with his own fragile identity. Palpatine’s observation, “Ever since I’ve known you, you’ve been searching for a life greater than that of an ordinary Jedi” perfectly captures Anakin’s restless drive for exceptionalism. For individuals with narcissistic traits, the idea of being merely “ordinary” feels intolerable, even shameful. Anakin doesn’t just want to be a great Jedi, he wants to be the greatest, the most powerful, the one who transcends limitation and rewrites the rules.

This ambition isn’t fueled by arrogance alone, but by a desperate attempt to escape the feelings of powerlessness and insignificance rooted in his traumatic past. In seeking greatness, he isn’t just chasing status, he’s chasing salvation.

After failing to save his mother 10 years later, Anakin’s fear of losing the people he loves is intensified into an obsession. The trauma of her death becomes a psychic wound that never heals, fueling his desperate need to control the fates of those closest to him like Ahsoka and Padmé. Because he never properly learned how to grieve and accept loss as a part of life, he pursued absolute power as a safeguard against the unbearable pain of loss.

Throughout Anakin’s life, he feels that if he loses Padmé, he won’t be able to go on. Anakin’s fear of losing Padmé is so strong that he is willing to kill anyone and everyone to save her. People with BPD will go to extreme measures to avoid separation. This manifests as being overly dependent, clingy and anxious. When they believe their relationship is falling apart, they may threaten self-harm or do other coercive and manipulative behavior to ensure that someone stays in their life.

Anakin sometimes exhibits traits of Histrionic Personality Disorder (HPD), another Cluster B subtype. People who are histrionic are seductive, emotionally intense and dramatic for the sake of gaining attention. Throughout Attack of the Clones, we see Anakin trying to seduce Padmé. At their first reunion, Padmé lets him know that his creepy staring is making her feel uncomfortable. Oftentimes, people who are Cluster B don’t understand how they are making people feel and struggle to respect boundaries.

Anakin has been limerent for Padmé ever since he first laid eyes on her and thought she was “an angel.” He has been thinking about her every day for ten years. People with Cluster B personalities are more likely to experience limerence (obsessive romantic feelings), especially those who are Borderline. In this scene, Anakin dramatically says that he loves Padmé so much that it torments him and he will do anything she asks to be with her.

“You are asking me to be rational. That is something I know I cannot do.”

Anakin’s emotions and insecurity are so overwhelming that they completely override his capacity for clear judgment. This reflects a common dynamic in individuals with Cluster B personality traits: their behavior may appear irrational from the outside, but internally, it feels necessary—like the only option. When emotionally dysregulated, especially under perceived threat or abandonment, they act from a place of survival rather than reason. Their logic is emotional, not analytical—and while it may defy external logic, it reflects a desperate attempt to regain control, soothe pain, or preserve a collapsing sense of self.

Anger

When people’s deepest fears begin to materialize, they respond with anger in a desperate attempt to regain control over a world that suddenly feels uncontrollable. Anakin’s rage reaches a breaking point after the death of his mother, Shmi. He unleashed fury onto the Tusken Raiders after they killed his mom. While his reaction may seem understandable, it also reveals a pattern common in individuals with narcissistic traits: a heightened tendency toward revenge and displaced aggression. Instead of processing his pain or directing blame appropriately, Anakin projects his anguish onto an entire group of people.

Padmé: “Sometimes there are things no one can fix. You’re not all-powerful.”

Anakin: “Well I should be! Someday, I will be. I will be the most powerful Jedi ever. I promise you! I will even be able to stop people from dying. It’s all Obi-Wan’s fault! He’s jealous! He’s holding me back!”

Narcissistic Grandiosity and Deflection

This scene captures how Anakin uses anger as a defense against grief and helplessness. Rather than sit with the reality of loss and limitation, he lashes out, grasping at fantasies of omnipotence. For individuals with narcissistic traits, trauma reinforces grandiosity, not humility. When wounded by life’s tragedies or rejection, they double down on the belief that if they were only powerful enough, they could prevent suffering, avoid shame, and stay in control.

Notice how the emotional sequence unfolds: Anakin begins with a hint of personal guilt and a recognition of his limits, but the shame that follows is intolerable. Rather than metabolize that shame, he redirects it outward, projecting blame onto Obi-Wan. This externalization is common in narcissism, especially during what’s called a narcissistic injury—when their inflated self-image is punctured. To preserve their sense of self, they may gaslight, distort facts, or vilify others. In this case, Obi-Wan becomes the scapegoat for Anakin’s inner turmoil. Taking responsibility would mean facing his own vulnerability, and for Anakin—as with many narcissists—that feels psychologically unbearable.

Narcissistic Rage

When the Jedi Council grants Anakin a seat but denies him the rank of Master, he reacts not with humility, but with outrage:

Rather than tolerate feelings of inadequacy or self-doubt, he responds with anger, entitlement, and an urgent need to reassert their superiority. In Anakin’s case, the Council’s decision doesn’t just bruise his pride, it feels like a denial of his identity as “the Chosen One.” Narcissistic rage is a disproportionate, emotionally charged response to a perceived injury to one’s ego.

Narcissistic Jealousy

Narcissists are prone to jealousy, stemming from a need to possess and control the people in their lives. They view others, especially romantic partners and their children, not as separate individuals, but as extensions of their own identity and self-worth. When that control feels threatened, jealousy escalates into rage. Here, Anakin wants to kill Rush Clovis. His reaction isn’t just about romantic rivalry, it’s about the ego injury that comes from someone else encroaching on what he considers his and the fear of losing Padmé.

Narcissistic Impulsivity

Because narcissists have a diminished capacity to sit in uncomfortable emotions, they are often frustrated with where they are at and act impatiently and impulsively. When fighting Count Dooku, his master tells him that they will fight together, but Anakin thinks he can take Dooku himself and eventually loses his arm as a result.

Narcissists, while often exceptionally talented in their area of expertise, still overestimate their skills, knowledge and abilities.

Anakin’s anger is psychological armor he wears to protect himself from fear, shame, and helplessness. Beneath each outburst are emotional wounds that he was never taught to understand, let alone heal. His rage emerges when he feels powerless, unseen, or humiliated, and rather than confront those raw emotions directly, he externalizes them through grandiosity, violence, and blame. This is the tragedy of unchecked narcissistic vulnerability: instead of reaching for connection or reflection, the individual reaches for control and domination.

Hate

For Anakin Skywalker, hate becomes the final refuge from the emotional chaos he was never taught to navigate. When fear and loss become too overwhelming, hate gives him something to hold onto—something that feels powerful, focused, and absolute. In choosing hate, Anakin believes he is protecting himself from further pain, but in reality, he is severing the final threads of his humanity. This psychological turn toward hatred is driven by the underlying cognitive distortion common in Cluster B personalities: black-and-white thinking.

Black-and-White, Dichotomous Thinking

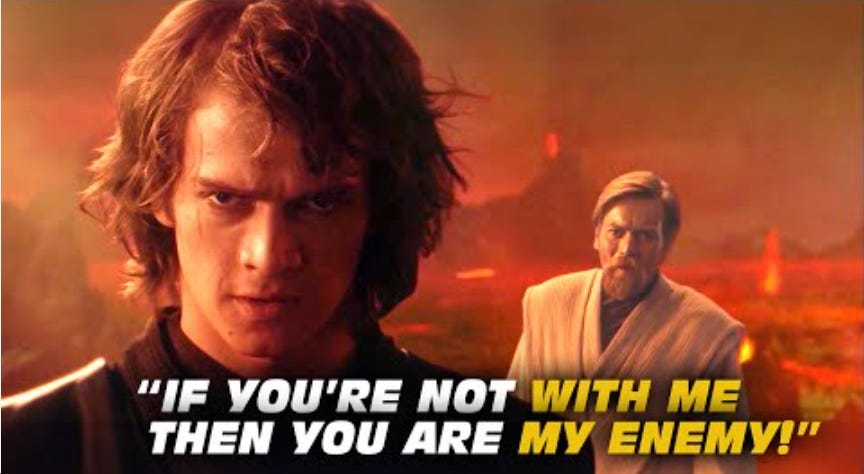

People with Cluster B personalities struggle with black-and-white thinking, also known as splitting—a defense mechanism where people, ideas, or institutions are seen as entirely good or entirely evil, with no room for nuance. This inability to hold conflicting truths in tension leads to rigid, absolutist beliefs that swing dramatically depending on emotional state. At first, Anakin is deeply devoted to the Jedi Order and believes in their righteousness. But as he witnesses their hypocrisy, political entanglements, and emotional repression, his idealization of the Jedi begins to collapse. Rather than processing these contradictions with complexity, he flips 180, suddenly viewing the Jedi as corrupt and Obi-Wan as a traitor. Like many with narcissistic or borderline traits, Anakin doesn’t shift to a moderate or balanced position. Instead, he adopts a new ideology with the same blind conviction he once gave to the Jedi. This extreme switch mirrors the way emotionally unstable individuals often attach themselves to new belief systems or relationships with absolute intensity, unable to tolerate ambiguity or emotional grey areas. In the span of a day, the Jedi go from heroes to enemies, and Palpatine goes from mentor to savior, without space for a middle ground.

Similarly, when Padmé pleads with him on Mustafar, Anakin’s mind abruptly shifts her from “the love of my life” to “betrayer,” and he chokes her—treating her not as someone he cherishes, but as a threat to be eliminated.

Have you ever had someone close to you turn on you all of a sudden, treating you like an enemy, attacking you without warning? This kind of abrupt shift is often a sign of an underlying Cluster B personality structure where their insecurity leads to abrupt changes in perception.

Self-hatred

People with borderline and narcissistic traits often struggle with intense shame and fractured identity, leading them to disown the parts of themselves they associate with vulnerability, failure, or rejection. For Anakin, the name “Anakin Skywalker” became a symbol of everything he couldn’t bear: his helplessness, his guilt, his grief over Padmé, and the unbearable realization that he had betrayed the very people he swore to protect. In killing off Anakin, Darth Vader is enacting a psychic annihilation, splitting off and burying the part of him that felt too weak to save those he loved. This is a form of psychological dissociation: when self-hatred becomes so overwhelming that the only way to cope is to create a hardened, emotionless identity to replace the self that was never allowed to be whole. Vader is not just the mask—he is the wound made sentient.

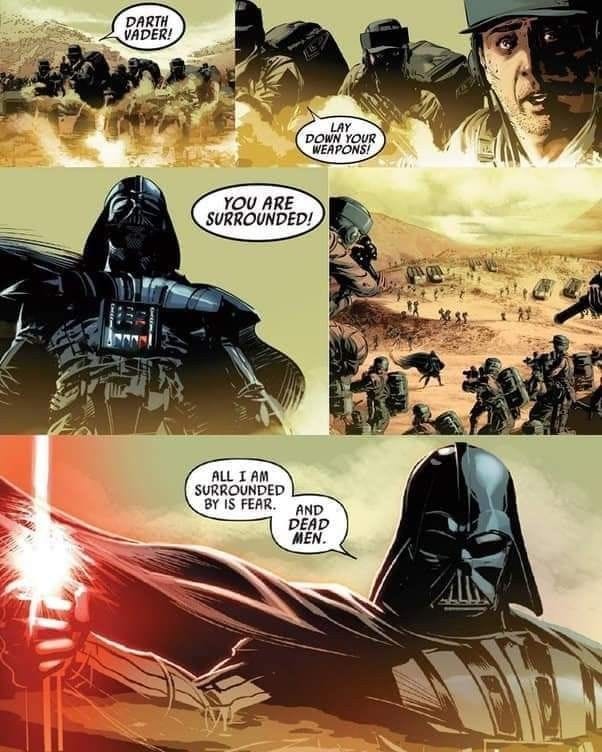

Unable to confront the depth of his own self-hatred, Vader turns that hatred outward. Rather than sit with the unbearable guilt, grief, and shame that define the shattered remnants of Anakin Skywalker, he projects those feelings onto the world around him. This externalization becomes a defense mechanism—by villainizing others, he avoids facing the parts of himself he has disowned. The galaxy becomes the enemy, the Rebels the embodiment of betrayal. In this way, Vader’s war is not just political or ideological—it is deeply personal. His need to dominate and destroy is a way to ignore his need to forgive himself.

Once he becomes Darth Vader his hatred toward rebels and the galaxy at large is fueled not just by political allegiance to the Empire, but by personal betrayal and a distorted need for control. In his mind, the Rebels are not simply dissenters—they are traitors to the order he sacrificed everything to protect. His identity is so deeply fused with the Empire that any challenge to its authority feels like a direct assault on him personally. For someone with narcissistic and borderline traits, any attack on an institution they identify with is experienced as a personal attack—because they see the institutions and beliefs they align with as extensions of themselves. This fusion fuels intense hatred toward dissenters, who are no longer viewed as individuals with differing views, but as enemies who threaten the narcissist’s fragile sense of control, identity, and significance. In Vader’s case, the Rebels aren’t just opposing the Empire—they are, in his mind, trying to dismantle him.

Suffering

Beneath the armor, the rage, and the facade of control, Anakin Skywalker, now Darth Vader, is suffering. His entire life has been marked by loss, abandonment, and emotional repression, yet no one ever taught him how to grieve, how to feel without being overwhelmed, or how to accept that pain is part of the human experience. Instead, he internalized the belief that suffering was a weakness to be crushed, a burden to be hidden. But that pain never left—it simply changed form. It hardened into anger, transformed into hatred, and calcified into the cold, mechanical breathing of Vader. Every act of violence he commits isn’t just a show of strength, but a cry of unresolved agony. His suffering is not only emotional but existential. He is trapped in an identity forged by shame, fear, and the illusion that power could protect him from heartbreak. Anakin didn’t stop suffering when he became Vader, he simply stopped letting anyone see it. The trap of the Sith, which is essentially a path of narcissism, is that at the end of the line, all you have left is yourself.

Anakin never lived a day without calling someone Master. First it was Watto, then the Jedi, and finally, Palpatine. Though he was freed from physical slavery, he remained psychologically bound, constantly seeking approval, direction, and belonging from powerful figures who reinforced his dependence. His need to submit to a “master” wasn’t weakness—it was the legacy of a boy who never learned how to trust his own voice or feel safe in his own skin. If Anakin had been given the tools to confront his inner wounds earlier, to grieve his losses and develop a stable sense of self, he might have freed himself long before putting on the mask.

Interventions: What the Jedi Should Have Done Instead

The Jedi Order failed Anakin by ignoring the emotional pain that fueled his need for more power. They preached detachment and discipline, but what Anakin truly needed was attunement, guidance, and emotional integration. Had the Jedi been more trauma-informed, emotionally literate, and flexible in their doctrine, the outcome might have been very different.

1. Acknowledge His Trauma

Rather than suppressing or dismissing Anakin’s early experiences of slavery and loss, the Jedi should have addressed them directly. A trauma-informed approach would recognize that Anakin’s attachment issues, fear of abandonment, and emotional reactivity were not just character flaws—but symptoms of unresolved developmental trauma. Therapy, mentorship, or even structured peer dialogue could have helped him process these wounds rather than bury them.

2. Support Secure Attachment

The Jedi demanded emotional detachment, yet Anakin was an emotionally intense and attachment-hungry individual. Instead of forbidding attachments, the Jedi could have modeled secure, non-possessive relationships and offered consistent emotional mentorship. Obi-Wan tried, but he was often emotionally restrained and bound by Jedi orthodoxy. Anakin needed not just a teacher, but a caregiver capable of offering safety while encouraging individuation.

3. Allow Emotional Expression

Suppressing emotion only deepens shame and intensifies dysregulation. The Jedi repeatedly taught Anakin to “let go of his feelings”, but never gave him the tools to understand, tolerate, or navigate them. A more effective intervention would have been emotion regulation training—mindfulness, distress tolerance, and cognitive reframing.

4. Challenge Black-and-White Thinking

Rather than promoting rigid binaries (attachment = bad, detachment = good), the Jedi could have taught Anakin to embrace nuance and ambiguity and elements of his shadow. Encouraging dialectical thinking—the ability to hold two conflicting truths at once—might have helped him tolerate the imperfections of the Jedi Order without flipping to complete disillusionment. This would also have weakened the allure of Palpatine’s absolutism. The most effective treatment for borderlines is Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) where people learn to tolerate ambiguity and find balance between extremes. After all, his destiny was to bring balance to the Force.

5. Create a Space for Confession Without Judgment

Anakin kept his secrets—his marriage, his fear, his rage—because he knew the Jedi would judge or expel him. Emotional healing requires psychological safety. The Order could have created a space where Jedi could speak openly about doubt, fear, love, and even failure—without losing their place. Shame thrives in secrecy. Compassionate mentorship and non-punitive guidance could have brought Anakin’s inner conflict into the light.

In the end, the Jedi Order upheld tradition instead of adapting to a changing galaxy. Anakin needed more than rules—he needed relational repair, emotional literacy, and secure connection. Without those, his extraordinary gifts became weapons turned first inward and then outward.

Anakin Skywalker, despite his character flaws, was a good person with a generous heart. If you’ve watched the Clone Wars animated series, you know just how much he cared for his friends, showed great loyalty, and often risked his own safety to protect others. His compassion for the oppressed and his desire to end suffering were genuine. In many ways, his narcissistic traits—his need to feel important, to be seen, to make a difference—were extensions of that same longing to help, but without the emotional tools to regulate his inner turmoil, that desire became distorted by fear and insecurity. Anakin’s tragedy isn’t that he was a monster—it’s that he was a deeply feeling human being who never learned how to carry the weight of his own emotions. As Vader’s ultimate redemption reveals, it is never too late to change. Healing is possible even for those who have lost themselves along the way. If you or someone you know struggles with emotional dysregulation, unstable identity, or relationships that feel out of control, you are not alone. There are people who care and want to help. Leave a comment below, or feel free to reach out to me directly at danielyee517@gmail.com. If you know someone who is a fan of Star Wars, please share this with them! May the force be with you.

This is truly a well-written piece on Darth Vader - once a hero who tragically fell due to his deep unresolved and compounding traumas.

Yippee!!! I loved this article so much.